GAW History

From The Beginning

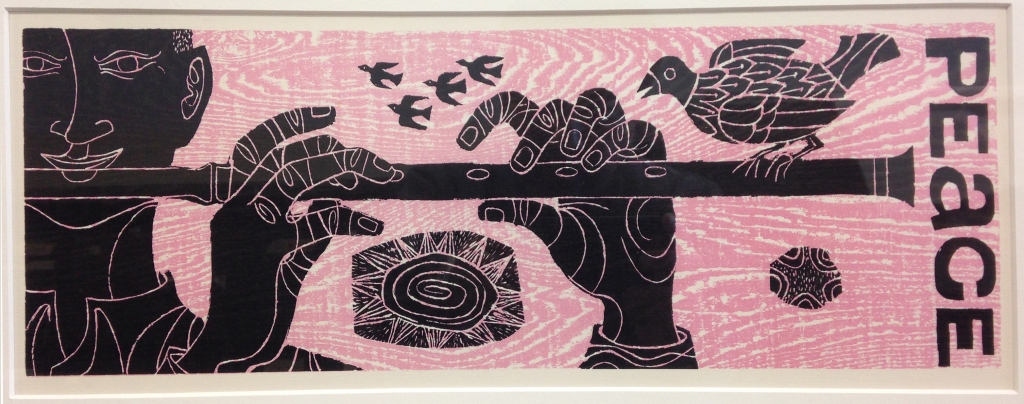

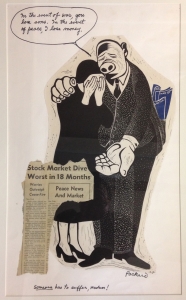

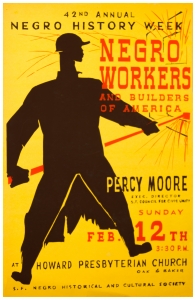

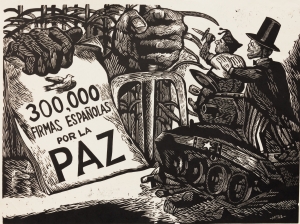

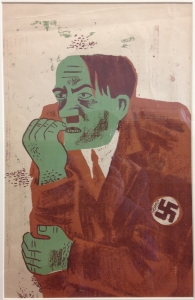

Graphic Arts Workshop was founded in 1952 by faculty and artists from the California Labor School. During the 1930s and 40s, the impact of the Great Depression, the WPA Federal Arts Project, and visiting Mexican artists as well as other European modernists had a profound impact on the new generation of print artists in San Francisco. The dominance of the etched or engraved line began to be eclipsed by other techniques such as lithography, relief, and serigraphy or screenprint. These new techniques were accompanied by an aesthetic move toward more socially engaged subject matter. The Graphic Arts Workshop (GAW) members’ societal concerns were reflected in each artist’s style of work and in the co-operative form of the Workshop. The printshop became a base of political activity and abundant artistic output, and attracted many foreign artists as collaborators.

Graphic Arts Workshop was founded in 1952 by faculty and artists from the California Labor School. During the 1930s and 40s, the impact of the Great Depression, the WPA Federal Arts Project, and visiting Mexican artists as well as other European modernists had a profound impact on the new generation of print artists in San Francisco. The dominance of the etched or engraved line began to be eclipsed by other techniques such as lithography, relief, and serigraphy or screenprint. These new techniques were accompanied by an aesthetic move toward more socially engaged subject matter. The Graphic Arts Workshop (GAW) members’ societal concerns were reflected in each artist’s style of work and in the co-operative form of the Workshop. The printshop became a base of political activity and abundant artistic output, and attracted many foreign artists as collaborators.

Founding Members

California Labor School

Formerly the Tom Mooney Labor School (it was renamed in 1944), the California Labor School was an educational institution in San Francisco from 1942 to 1957. In its heyday, the California Labor School (CLS) was supported by 72 trade unions, members of the American Federation of Labor and the Congress of Industrial Organizations, and served as a center of labor activism that offered a range of classes to working people and returning World War II veterans. Its initial program, openly Communist in its founding principles, “promised to analyze social, economic and political questions in light of the present world struggle against fascism.” It also taught the arts and, at its peak in 1948, the school had an art department that was nearly as large as the California School of Fine Arts (now The San Francisco Art Institute). The CLS attracted instructors from all over the world such as: Pablo O’Higgins, the American-born co-founder of the TGP (Taller de Gráfica Popular or People’s Graphic Workshop), who taught there in 1945 and again in 1948, and was student of Diego Rivera; and the Italian-born Giacomo Patri, who created the iconic print series of the Depression with his wordless novel of linocuts, White Collar (1938), and was head of the Art Department of the Labor School starting from 1947.

Formerly the Tom Mooney Labor School (it was renamed in 1944), the California Labor School was an educational institution in San Francisco from 1942 to 1957. In its heyday, the California Labor School (CLS) was supported by 72 trade unions, members of the American Federation of Labor and the Congress of Industrial Organizations, and served as a center of labor activism that offered a range of classes to working people and returning World War II veterans. Its initial program, openly Communist in its founding principles, “promised to analyze social, economic and political questions in light of the present world struggle against fascism.” It also taught the arts and, at its peak in 1948, the school had an art department that was nearly as large as the California School of Fine Arts (now The San Francisco Art Institute). The CLS attracted instructors from all over the world such as: Pablo O’Higgins, the American-born co-founder of the TGP (Taller de Gráfica Popular or People’s Graphic Workshop), who taught there in 1945 and again in 1948, and was student of Diego Rivera; and the Italian-born Giacomo Patri, who created the iconic print series of the Depression with his wordless novel of linocuts, White Collar (1938), and was head of the Art Department of the Labor School starting from 1947.

1945-1957 The Dark Years

From 1945 to 1947 the school was accredited for veterans’ education under the G. I. Bill of Rights, and by 1947 there were 220 full time students, among the 1800 students attending 135 classes. Dr. Holland Roberts, the School’s Educational Director, in a draft manuscript of his memoirs, described 1948 as “the School at its peak.” That same year, however, the U.S. Attorney-General placed the California Labor School on the Subversive List and thus began a ten-year attack led by the Subversive Activities Control Board in the Department of Justice and other government agencies. Once the School was labeled subversive, a student could not be employed by the federal government or any institution which had a “loyalty oath” in place. If a student worked for the government, he or she could be discharged. Not surprisingly, dwindling enrollment and meager class offerings forced the school to close in 1957.

From 1945 to 1947 the school was accredited for veterans’ education under the G. I. Bill of Rights, and by 1947 there were 220 full time students, among the 1800 students attending 135 classes. Dr. Holland Roberts, the School’s Educational Director, in a draft manuscript of his memoirs, described 1948 as “the School at its peak.” That same year, however, the U.S. Attorney-General placed the California Labor School on the Subversive List and thus began a ten-year attack led by the Subversive Activities Control Board in the Department of Justice and other government agencies. Once the School was labeled subversive, a student could not be employed by the federal government or any institution which had a “loyalty oath” in place. If a student worked for the government, he or she could be discharged. Not surprisingly, dwindling enrollment and meager class offerings forced the school to close in 1957.

A New Beginning

Before the doors were forever closed however, the artists and some of the CLS faculty moved the litho presses and other equipment to a studio on Francisco Street in North Beach and Graphic Arts Workshop was formed. Early members of the Workshop pursued social justice through the graphic arts, printing posters, pamphlets, and calendars in support of various causes (and later, against the War in Vietnam). Early members such as Victor Arnautoff and Emmy Lou Packard had close connections to Diego Rivera. The WPA tradition of linking printmaking and murals was still strong and lasted long after the link was broken in other places. Anton Refregier, who painted the last WPA-funded mural in the country—at Rincon Annex in San Francisco—was assisted by Louise Gilbert, both of whom were GAW founders and had taught at the California Labor School.

Over the years, at various locations, many fine artists—among them founders Stanley Koppel, Pele deLappe, Irving Fromer, Frank Rowe, Louise Gilbert, Victor Arnautoff, and Emmy Lou Packard — produced their own prints as well as political posters.

Over the years, at various locations, many fine artists—among them founders Stanley Koppel, Pele deLappe, Irving Fromer, Frank Rowe, Louise Gilbert, Victor Arnautoff, and Emmy Lou Packard — produced their own prints as well as political posters.

“The goal was to do socially necessary work,” said Pele deLappe at the Workshop’s 50th Anniversary Show, “Proof(s) of Life: The Graphic Arts Workshop 1952-2002,” at San Francisco’s Meridian Gallery.

“We believed art should have political significance to it, rather than just be a pretty picture,” said Louise Gilbert, who made many prints about the ’34 strike and posters for civil rights and grape-boycott rallies.

In her own work, de Lappe stated “I would do something that agitated people—to take action about peace and justice and all those glorious things. Especially against racism. I did lithographs that had all those themes. I’ve always been concerned about people. That’s why I never became an abstract expressionist; my subject was always solidly rooted in people. I dig people.”

That kind of dedication amongst the early members of the Workshop had a cost. The anti-Communist zeal of the late 40s and 50s intimidated many artists and effectively discouraged art of any dissenting or political nature. Artists, across all disciplines, became the subject of aggressive investigations and questioning. Several artists of GAW were harassed by the FBI.

GAW Today

In 1973, due to internal struggles, GAW formally moved away from direct political affiliation and decided to focus on simply providing an environment for members to pursue their own artwork. At its present location in the American Industrial Complex in the Dogpatch neighborhood of San Francisco, the Workshop has since fostered a strong sense of individual visions.

In 1973, due to internal struggles, GAW formally moved away from direct political affiliation and decided to focus on simply providing an environment for members to pursue their own artwork. At its present location in the American Industrial Complex in the Dogpatch neighborhood of San Francisco, the Workshop has since fostered a strong sense of individual visions.

Today the Workshop is a cooperative of approximately 26 artists working in a variety of printmaking techniques. In its steadfast commitment to continue to provide a place for printmakers to work and collaborate, the Workshop has adapted to numerous financial constraints and the volatility of the San Francisco real estate market to house its members. Over the years, GAW membership has included many distinguished artists, undertaken national and international art exchanges, and hosted traveling exhibits. A quote in a pamphlet from a History exhibit held in 1989 at GAW’s former home and gallery on California Street offers this sentiment which comes full circle in echoing the mission of GAW today:

Today the Workshop is a cooperative of approximately 26 artists working in a variety of printmaking techniques. In its steadfast commitment to continue to provide a place for printmakers to work and collaborate, the Workshop has adapted to numerous financial constraints and the volatility of the San Francisco real estate market to house its members. Over the years, GAW membership has included many distinguished artists, undertaken national and international art exchanges, and hosted traveling exhibits. A quote in a pamphlet from a History exhibit held in 1989 at GAW’s former home and gallery on California Street offers this sentiment which comes full circle in echoing the mission of GAW today:

“In all this, there were no imposed styles or themes. Artist-members as individuals worked freely with a diversity whose common element was the love of printmaking.”